Mark Kraushaar’s work has been included in Best American Poetry, Ploughshares, and Yale Review as well as the web site Poetry Daily and Ted Kooser’s American Life in Poetry. He has been the recipient of Poetry Northwest’s Richard Hugo Award. A full-length collection Falling Brick Kills Local Man (University of Wisconsin Press) was the winner of the 2009 Felix Pollak Prize. His collection, The Uncertainty Principle (Waywiser Press), was chosen by James Fenton as winner of the Anthony Hecht Prize.

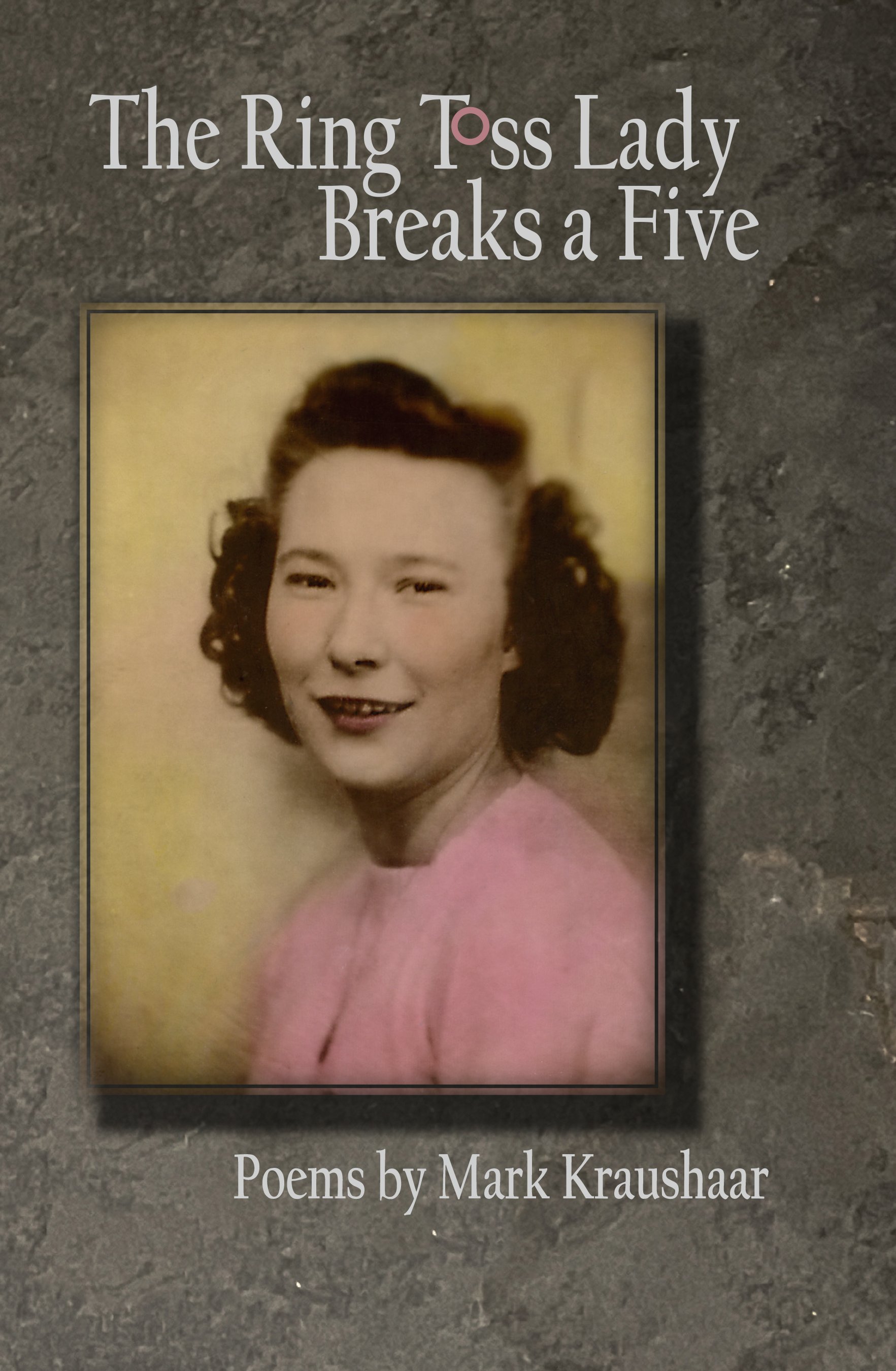

Selected poems from The Ring Toss Lady Breaks a Five

Larry something, 13b

Just before disco and after the Beatles

I took the Greyhound bus to a town in Vermont.

I got a room and found work.

I walked a lot.

There was a Larry something lived next door.

Wheaton, was it? Wooten?

We shared a wall; we shared the view:

a Mobil station plus a patch of weeds.

Larry liked to say he’d been around.

Back when … he’d start, In my time … he’d explain

then show me photos:

Chevy Nova, classmate, Army days.

A tippler, reclusive and gentle, he seemed

a kind of incidental flowering himself.

Oh, I’ve lived he’d say, but it’s like I’ve disappeared,

I’m frightened anymore, I don’t get out—

I should, I don’t.

Still, Larry loved to fix things—mowers, TVs, toasters—

then one day inviting me in to scope a junk-picked Barca lounger

we stepped out for air on his balcony,

a creaky iron walk no wider

than a folding cot, when just below us

from her truck, the mail lady waved.

It had rained, the sun was out and Larry,

at rest on a milk crate, wanting to wave too,

starting to stand, staggered and sat back, not drunk

but as against the movement of the world.

Weyland. Larry Weyland. Sure.

What If The Hokey Pokey Really Is What It’s All About?

You put your right foot in,

You put your right foot out…,

That’s what it’s all about.

—“The Hokey Pokey,” Larry LaPrise, 1948.

Of an evening filled with wide-set

bright stars I think of my friends, Ray, Sara,

Father Hay, and Phil and Joe.

I think of them together and I think of them alone:

Friends, what better than to put your right foot in,

and what better than to take it out again?

What better than to leave your jacket

and your drink and join

the circled strangers on the floor?

What better than to put your left foot in

and then to take it out since

who’ll explain this strange life anyway,

the problems with love, the trouble with money?

It must be what is meant, this must be what’s intended.

What better than to leave your silent trying behind

and put your right foot in once more

then shake it all about?

What better than having said too little

or too much you join the farmer with his wife

and daughter, the couple with their

squeaky walkers, the Fed Ex man,

the florist and the LPN?

It must be what is meant,

this must be what it’s all about:

what better than to join the high-heeled,

high-haired waitress first pausing and laughing,

then leaning to her friend, the grinning busboy

who, putting his elbow in then out again,

now shakes it all about.

Worry

A big woman, forever ready with advice,

thick, high hair gone grey, Donna lives across the hall

and tells me what to eat—greens, fish, fresh fruits,

no meat, no sweets.

Then one day I’m home after work when she knocks,

knocks again then rattles the knob

as I crack the door.

You’re always so serious,

have a plum.

Frowning, turning sideways,

she scoots straight past me, then stands

beside the fridge, puffy eyelids, mail slot mouth.

I know you worry, Mister,

but because I’m older I

can tell you this:

if you hear a siren take a breath.

If you see a car wreck touch your right first

finger to your thumb and say, Om.

Where’s the harm? she asks.

I know you worry what will happen—and I know

you worry what will happen afterwards.

One day you

become a concentration of yourself,

a concentration but a dilution too.

Take my word, I’m older and I know:

I tell you, sit beside the window, wear your

billed cap backwards.

It’s for the world

and for those run over by it.